Blog

Phixing A Phat Dysphunctional Pharma Contract Manufacturer and Avoiding Phailure

June 26, 2021

Phailure.

This was a global, private equity-owned CDMO that was failing (Or, if you prefer, phailing) fast.

This business was generating more than $350 million in revenue.

But, it was generating losses, losses that were mounting.

What’s a CDMO? A pharmaceutical contract development and manufacturing organization.

And, this particular CDMO was literally a few weeks away from running out of cash when I was asked to join as CEO. I’ve never cared about titles. This one came with a significant amount of responsibility, risk, and opportunity. It was in a highly regulated industry that focuses on patients relying on their medicines.

I’ll call the company Brie Pharma.

Why brie? Well, it’s crusty and hard on the outside, soft on the inside, doesn’t have much of a taste, but it stinks pretty bad if it’s left alone unattended.

Brie was simply, a roll-up of several unrelated legacy assets that were divested from big pharma.

Prior to the impressive responsiveness the pharma industry exhibited in WarpSpeed, it’s never been an industry known for its speed or low cost delivery models.

Unless I was missing something, I saw no apparent synergy in this cobbled together group of unrelated assets divested by Big Pharma.

I was the fix-it guy working for a dysfunctional ownership group plagued with internal problems. I saw a business struggling under the weight of a variety of challenges, not the least of which was poorly structured asset acquisition deals and teetering on insolvency. A layer cake of board-sanctioned mismanagement which happened on the board’s own watch.

Other challenges included rigid employment and workforce contracts and assurances, financial and operational disconnects in the sites that were acquired, wild spending — including high IT spend, inefficient energy consumption across plants, enormous looming cash requirements to fund high payrolls, and balloon and installment payments for acquiring the sites through creatively financed seller notes.

This rollup model looked less like a strategically driven company and more like the nail technician that went to a Tom Wu seminar and owned 12 homes in 5 states with no money down in some 80’s mortgage-a-palooza.

But, this wasn’t real estate, it was pharma, or, healthcare, and, like an unfortunate healthcare patient, it was bleeding.

It needed first responders. Those first responders would be our turnaround team and a cadre of key legacy employees who embraced the challenge and the change and who came alive and came to action.

Having little pharma experience was one of the most important success factors that drove the turnaround.

No bad habits, no industry filters or myopia.

Brie had great people.

Brie had people that were fearful.

Some of them, including most of the senior team which was a model of a lack of diversity — 15 well off semiretired white guys in their 60s.

Some ran away, terrified. We also had fearless, brilliant, resilient people. Great employees. They just needed to be led toward clearly articulated goals to improve financial and operating results.

So, we began the transformation.

I had the good fortune to work with a team of strong advisors.

While the personalities and egos often clashed, in the end, the results were stellar, and it was only through building on the basics of Plan, Organize, Motivate, and Control (POMC) that sound management practice, tireless work, and the ability to humbly admit all I/we didn’t know and focus people much smarter than I on all we needed to fix, were some of the ingredients to our success.

A little bit of alphabet soup. This was, after all, the pharma industry, which loves acronyms.

In addition to the POMC — there was one more C — Communicate. I figured out that if I didn’t reach out, get out there and communicate and earn the trust and confidence of the customers, the regulators, the employees, the bank, the other stakeholders, I, we, and the turnaround itself, were doomed.

One thing resonated with me above everything else — the P — the Patients. We were all ultimately accountable to them. That was the foundation of our program of change — that we shared with our stakeholders — especially the big pharma companies whose names and brands were on the bottles, boxes, packages, vials, ampules, and pills we produced — that we were unified in the drive for the big S — Sustainability. Here’s a little glimpse into the transformation of Brie.

A transformation that needed to happen quickly, as Brie was starting to stink, like, well, Brie left out in the summer sun. Phew.

A TWO-SIDED LADDER

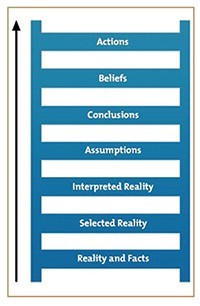

When you do turnaround work, interim CEO work, and/or any kind of organizational change, you inevitably find yourself in the midst of a two-sided Ladder of Inference problem.

The Ladder of Inference was first put forward by organizational psychologist Chris Argyris and used by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. The Ladder of Inference describes the thinking process that we go through, usually without realizing it, to get from a fact to a decision or action.

On the one hand, you can easily jump to conclusions and have preconceived notions, as the change agent; on the other side, the industry veterans can quickly dismiss your lack of industry knowledge as a major risk or failure factor, or it just may be a response to their own fears.

Why two sides?

Well, you as the change agent view the steps and the sequence of the rungs in the ladder one way, and the other folks see it differently. But that’s ok. From either side, success can only come from being rooted in reality. Reality and facts (and factual evidence) are at the base of the ladder. From this point of “safety,” where we’re closest to the ground, we begin to ascend. As we go up, we must look at facts, isolate our beliefs and prior experience, and draw conclusions based on hard data, and be prepared to take objective actions. That’s hard for people to do. Change is difficult. It’s human nature to page ahead in the test, to skip scenes while watching Netflix, to wanting to know what happens at the end of a book.

A challenge in the company in question is across sites and geography, “sets” of employees would undoubtedly have preconceived ideas. That is further complicated by what a prior management team (most of whom aren’t there anymore) told them, and whether they identified, or disagreed with, those perspectives. Did they know what a plan was? Did they agree with it? It doesn’t matter because now they were in the midst of another change — a new CEO and perhaps other new executives, site heads, functional heads, etc.

All of the stakeholders of the CDMO — the bank, lenders, vendors, employees, shareholders, customers, former legacy owners (some of whom are creditors with seller notes) — have wildly varied beliefs, experiences, judgment, and degrees of openness of mind.

And there was $150 million of debt to restructure, which seemed more like a wooden ladder heading down into Dante’s Inferno. The board was starting to feel the heat and the lick of the flames. Or, if you prefer, phlames.

The point of The Ladder of Inference is to force objectivity and get consensus to move a team of people forward in unison, to respond to and manage challenges. Some of the employees thought I was insane. Some thought our entire team was insane. Some didn’t understand what we were doing. Some didn’t care. Some just left. Some checked out. But most dug in, buckled up, let go, and hung on. And when they first witnessed positive impacts, they realized they didn’t have to be fearful.

PHLAWED ASSUMPTIONS

Brie was one of many companies with business models that worked better in theory than in practice. Why? Flawed assumptions. Or, if you prefer, phlawed. When big pharma began selling off their large plants, the premise was that some entrepreneurial companies called CDMOs would own the plants, and the former cost centers would magically become vendors overnight.

Uh, no. Not so simple, especially if the products made in those plants were about to become cheap generics, or the plant was just operating far under break even capacity.

And, then there were the legacy cultures.

The reality was that the legacy cultures had high inertia. How do you magically turn a 20- or 25-year employee of some huge global pharma company into an overnight entrepreneur? It’s like taking a person who has played hockey for 25 years and asked them to be a pilot or Formula One (or, if you prefer, Phormula One) driver the next day. You might have a new business card that says you work for an airline or a race team, but you’re still probably thinking about playing hockey.

The transition to get former legacy-owned plants to independence and profitability was a challenging one, and, like most industries that have been through deregulation, or whose largest players have spun off or spun out assets, the devil is in the details, normally embodied in the fine print of the contracts the divestiture was “papered” with, such as an asset purchase agreement (or asset sale agreement), master services agreement, or transitional services agreement.

Legacy plants are overbuilt, inefficient assets that were run as cost centers of big pharma. After acquisition by a CDMO, they are magically supposed to be efficient, low-cost production centers. This poses challenges from a number of perspectives, the capital itself (buildings, facilities, equipment, machinery) and the workforce.

Transitioning the workforce culture from a bureaucratic pharmaceutical industry to an entrepreneurial “low-cost but high-quality” nimble CDMO model poses many challenges. Pharma employees are highly compensated, and benefits are extremely generous, compared to most subcontracting businesses in other industries. With such high direct, indirect, and SG&A labor cost input into the model, it becomes very difficult to be profitable as a true low-cost provider.

Pharma organizational structures and staffing models are robust — with high span of control duplication, further bolstered by regulatory requirements and the pharma mindset, which was to overbuild, overstaff, and throw resources and people at problems and inefficiencies. The most profitable CDMOs have embraced a culture shift, injecting the mindset with new methodologies, operational excellence, more laser-focused KPIs, and flatter organizations, to cut cost, improve margins, and ultimately lower the cost of drugs for their customers, the pharma companies, and the ultimate customers — the P — Patients.

Workforce culture can be a major stumbling block for companies looking to make the transition from former big pharma cost center, or a purpose-built production facility dedicated to a single blockbuster drug, to a nimble, flexible low-cost provider. These two realities exist in conflict. Getting a long-term employee who’s never felt career risk or who has never been asked to double or triple their productivity over a period of time to embrace change remains a challenge.

In order for this turnaround to be successful, we had to accelerate the rate of change and the adoption of new mindsets within the company as a whole, but in more granular fashion, at the sites.

The sites were where the culture was most embedded. And all the sites came from different pharma legacy companies, which posed an integration nightmare.

Culture clash.

The large legacy pharma companies divesting the plants, and many of the CDMO startups that have acquired them, have found out that the typical 2- or 3- year transitional services agreement — a window of time that the acquirer presumes it can drive new business to the plant — is simply not enough time to transition the business.

Professionals on both sides of the arrangement — the supply chain and procurement people at pharma companies, and the people now working for the CDMO that was once a pharma cost center — agree that the time it takes to stabilize the spun off plant with enough diversified commercial business to produce net income and EBITDA — the main profitability KPI for CDMOs — is more like 6, 7, or 8 years.

A jointly crafted, fair, flexible, longer term site acquisition/supply agreement/asset purchase agreement, which places patient needs, sustainability of supply, and product quality above a hastily conceived divestiture/acquisition to get a plant off the books (or on the books in the case of the acquiring CDMO), would be most important to ensure future success. We had to point in that direction — pragmatic sustainability — as “true north.”

THE TURNAROUND OF BRIE

Our turnaround team immediately went to work on all aspects of operations in the US, Canada, and Europe, which included a deep review of the purchase agreements and supply contracts under which these former legacy sites had been acquired from the elite top list of “big pharma” companies.

While the CDMO’s revenues grew rapidly in just a few years, the facilities had not yet been integrated to save costs and leverage capabilities. Most of the sites were unprofitable, equipment was old, and the company had severely missed its internal forecasts on revenues, gross and net profits, EBITDA, and new customer sales.

And, the board had an aversion to any investment in capital.

The turnaround took a multi-pronged, site-specific approach to remedying the business model challenges along with the accompanying reputational issues. At the exact same time, mold was detected in a European operation, necessitating an immediate shut down and expensive eradication program, for an additional combined loss of 2 million Euros/month. The company’s prime lender, a bank, was soon fatigued, which brought new pressures to the situation. While vendors started holding shipments, the company was locked into rigid supply agreements, labor contracts, and other constraints that made it difficult to operate and nearly impossible to generate profits. EBITDA was negative. The media and the European unions were beating us up.

In some cases, so were the executives from the legacy owners, but we pushed through it.

The plan to restore Brie took dramatic measures to optimize revenue and margins while cutting costs. A discrete diagnosis and turnaround plan were created for each subsidiary. I sought out and personally met with each key customer, legacy company management contacts, and key supply chain vendors in order to build credibility and establish trust and retain vital lifelines to new commercial opportunities. As the turnaround took hold, Brie restructured corporate and site-based staff to make sure every key management function was efficiently and effectively covered.

Brie’s eight global sites varied by location, legacy company, production focus, company culture, and most importantly, the relative sustainability of the contracts associated with the acquisition of each unit. It would prove the best strategy to turn the company around would be to focus on each site’s unique pluses and minuses, and determine which sites would be retained and fixed, and which ones divested.

The newly energized and focused team went to work on revenue improvement and cost reduction opportunities, while ensuring compliance with intensely regulated quality and delivery guidelines, with the main metric being “on time and in full, or OTIF,” THE contract pharma benchmark KPI.

Since the end of FY2019, Brie has produced over $80 million in EBITDA.

PROBLEMS TO SOLVE

There were numerous issues plaguing the acquisitions which included the following:

- Rigid asset purchase agreements that restricted commercial opportunities, prohibited headcount reductions, and titular changes

- Sites that were grossly underutilized, with large excess capacity, producing late lifecycle products approaching or past the dreaded pharma “patent cliff” (Many pharma plants that ramped up for COVID related production are now entering “COVID Cliff.”)

- Contract pricing and volume design that frontloaded obligations from former legacy owners for sustainable volumes for a very short term

- An unrealistic forecast for commercial opportunities coupled with a grossly undersized sales team. The company’s main competitor has 40 plants and 200 sales people, a ratio of 5 per plant. Brie had 3 people covering 9 plants, a ratio of 1/3 of a salesperson each.

- Sizeable capex obligations due to deferred maintenance, poorly executed contracts for new business requiring Brie to expend large sums to “buy business” from other pharma companies willing to transfer their commercial production (manufacturing and packaging) in exchange for low pricing, and large commitments to buy machinery and equipment

- Large deferred obligations, such as balloon payments, substantial seller note obligations, and other acquisition financing arrangements that severely impaired near-term and long-term cash flow

- Excessive spending on IT (opex and capex) — A $22 million spend on SAP integration failed miserably and we insourced much of the support, cutting $5MM a year in spend.

- Excessive spending on HQ facilities and staff

- Ineffective sales and marketing — the company was focused on brand leadership above its size and scope when what it really needed was sales

- In addition, Brie was in covenant violation with its bank, and the relationship was strained

THE FIRST 10 DAYS

- Reduce headquarters line and staff officers’ headcount — Complete

- Recruit global restructuring team — Complete

- Cease all non-critical spending — Complete

- Contact Customers/Seller Note holders — Complete

- Cease payments and begin negotiation of seller notes — Complete

- Freeze all past due payables — Complete

- Model Proforma forecast 2019 — Complete

- CEO to visit every facility — Complete

- Cease IT projects and reduce IT spend — Complete

- Replace law and accounting firms at lower rates — Complete

- Replace overpriced IT through insourcing — Complete

- Move HQ; sublease corporate office — Complete

- Establish supply chain credit programs with vendors — Complete

- Stop losses in factory №8 within 30 days — Complete

- Stop losses in factory №7 within 30 days — Complete

- Gain customer financial support for Factory №6 — Complete

- CEO to visit every customer — Complete

- Accelerate A/R Collections — Complete

- Limited headcount reductions/consolidation/attrition — Complete

- Wage and benefit alignment — Complete

- Consolidate certain senior management positions — Complete

Of those action steps:

- HQ headcount reductions produced an annual EBITDA improvement (Salary, Bonus, and Perquisites)

- Lease termination generated a savings, boosting annual EBITDA

- Cancellation of certain corporate events and trade shows produced an annual EBITDA improvement

- Divestiture/administration of certain European sites created tens of millions of annual EBITDA improvement

- Marketing expense was reduced by $1 million per year

- Renegotiation of supply agreements at four US sites improved EBITDA by millions annually

- Renegotiation of the maturities of seller notes and certain accounts payable

- Restructuring and insourcing of the expensive IT program and negotiated stretch-out of the high accounts payable related to prior IT expense with legacy IT vendors

- In-depth, on-site review of each operation to explore opportunities to reduce costs and drive production and revenue

- Freeze on all hires

- Review of all insurances and health care policies with a new Broker of Record to eliminate excess costs and improve coverages and increase employee participation in premiums

- Consolidation of executive roles and elimination of duplicate roles

- Reduction of millions in IT capex spend

- Reduction in IT contractor fees

- Reduction in audit and legal fees

- Streamlining and consolidation of common vendor contracts

- Drawdown sale and shipment of excess inventory to customers to reduce on- hand materials and improve cash flow and cash on-hand

And the digging in, and the savings and EBITDA restoration, would continue to bear fruit.

RESULTS: BRIE SAVED & RESTORED: SUSTAINABILITY FOR PATIENTS

In 12 months, Brie was successfully transformed, improving its relationship with its lender and vendors, maintaining critical mass with employees, retaining and improving (through contract renegotiation) all supply contracts with its customers, and regaining the confidence of its current as well as pending and new commercial customers.

By strategically downsizing to four sites from eight, Brie shed loss-making entities and improved Year-Over-Year EBITDA by increasing it from negative $45,000 to positive $32 million. The majority of the 1,900 jobs were preserved as employees left through attrition or returned to prior legacy company payrolls for those sites divested or returned.

Brie was efficiently and promptly restructured without resorting to a bankruptcy court filing for the entire group and without a change of control transaction. Administration court filings were made only for certain European subsidiaries, but an out-of-court restructuring was possible due to frequent communications and negotiations with the company’s bank and other key creditors.

Our major risk was from an IT vendor that threatened to shut down computer systems, wiping out supply in over 40 countries. After sensible, calm negotiation, this too was resolved peacefully. The community and industry in general were positively impacted by this turnaround. Industry supply was secured. Communities were protected even through the process, one of the European facilities was restored to health with mold eradication, Canadian and European facilities were sold, which protected those communities and the accompanying union jobs.

As a consequence, customers were happy, jobs were protected and secured, employees had been stabilized, and the bank was pleased. Most importantly, patients can depend on a stable supply of their medicines from a quality-driven, compliant, sustainable business operated by skilled, motivated, passionate employees. That’s the win!

SUMMARY: ALPHABET SOUP

The X factor in this transformation of Brie was the openness of employees. It was their willingness to embrace the agents of change and to listen and learn. I wasn’t the solution. The rest of the turnaround team wasn’t the solution.

The employees who had the intestinal fortitude to adhere to the plan, be part of the solution and not the problem deserve the lion’s share of the credit.

They accepted the challenge.

They accepted the change.

They accepted me.

They accepted us.

It was my pleasure to serve as the CEO and I back and take pride in what we were able to do and look forward to my next challenges. And meanwhile, the CDMO industry will likely continue to consolidate, creating both competitive intensity and opportunity, and hopefully greater focus on sustainability as patients rely on the industry for life-saving and life-enhancing medicines.

POMC works in the CDMO. POMC delivers OTIF. Nobody in the industry can ever forget the big P — the Patients, and the big S — the Sustainability of CDMOs.

Pharma thinks it’s a unique industry. It isn’t any more unique than every other one of the 30+ industries I’ve worked on.

We live in a world of flashy guru-speak and televangelist approaches to business, but if you’re fixing a business of any size or complexity, you need to ensure the presence of the right people in both governance, and management roles, and have common sense approaches to managing fundamentals.

Or, if you prefer, phundamentals.

Amazingly, the company has not changed its governance or improved its board, which, other than poor management and a wobbly strategy, was the real problem

Fascinating. Or, if you prefer, phascinating.

REFERENCE

- Argyris, C. Overcoming Organizational Defenses: Facilitating Organizational Learning, 1st Edition,©Printed electronically and reproduced by permission of Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. and Sons, Inc.

Need to grow, fix or exit your business?